I’ve probably ready both the second and third editions of Daniels’ Running Formula at least ten times each. The formulaic nature of the book is comforting, but I also had a hard time believing in the idea that there were only three paces that produced worthwhile stimulus. I hold true to that instinct, as I think the biggest gains I’ve seen in marathoning have come from running longer efforts in what he would consider a “junk mileage’ zone.

At one point I saw no value in thinking about runs in terms of time vs. mileage. I also so little value in prescribing work in terms of zones such as threshold or VO2 max and instead used more of a race-pace based system of 10k-pace, half marathon-pace, etc. I think a lot of great coaches use this method, but the more I reflect on training the more I realize many of those coaches are coming from a place where they are coaching high level athletes at a very similar ability level. If you are a high level college coach, 5k-pace means more or less the same for most people on the team.

I have since adapted my way of thinking much more to quantifying work based on thinking about what zones are most effective in producing stimulus from a time perspective. For example, an elite marathon may run 10 x 1 mile at threshold pace with one minute rest. Thinking about that from a time perspective, that would be 10 x ~5 minutes at one-hour pace with a one minute test. If you would try to transfer a similar workout to a 3:00 marathoner, 10 x 1 mile would be more like 10 x 6.5 minutes at a pace that isn’t necessarily optimizing work at your threshold.

The idea that a more pedestrian runner would be doing 65 minutes of work vs. an elite’s 50 minutes in roughly the same “zone” is insane, but it’s a trap I’ve fell into many times before. I’d now argue a better workout attacking the same stimulus for the 3:00 marathoner might be 6-7 x 1200 at threshold pace. It doesn’t sound nearly as sexy, but it is probably a better dosed stimulus that would elicit a more appropriate response and recovery time compared to higher volume work.

The same goes for easy running. Elite marathoners often run the main run of an easy day in about 70 minutes covering 10 miles. For a long time I thought the 3:00 marathoner should be pushing to cover 10 miles as well, but is running 10 more minutes on an easy day for a 3:00 marathoner a good thing when comparing it to an elite runner who often has a life infrastructure set up to maximize recovery? Probably not. Should a 3:00 marathoner even be running the same 70 minute run as an elite? Again, probably not, but you get the point. Time is a much better measure of stress than mileage for that reason. There is a time for specific work, but not nearly as much as I once thought. Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.

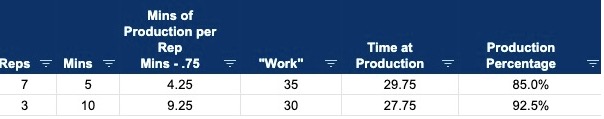

As I mentioned before, I think all paces exist on a continuum and every pace of running is worthwhile and produces some results. Prescribing work based only on the three or four paces from Daniels is leaving quite a bit on the table. However, I do think when assigning work, a better way to think about total workload is using time and pace range from a physiological zone approach. 6 x 1 mile at half-marathon pace could mean two very, very different things for different runners. However, 6 x 5 minutes at threshold evens the playing field and allows one to think about appropriate dosage for the level of the athlete.

I, too, was once mileage conscious all the time. However, I don’t care much about mileage at all on a weekly basis at all. High School coach John O’ Malley has contributed to a lot of the way I think about these ideas.

Hypothesizing a lot of his principles:

The human body doesn’t know mileage, but it does know stimulus, stress, and recovery.

So many things outside of training go into what the body is interpreting as stress.

As comforting as a calendar that lays out the perfect program is, it also assumes that life and response to training is the same for everybody and easily predictable. We’re all just using our best guesses to figure out what works best.